Lease term

Bringing leases on-balance sheet under NZ IFRS 16 - how long is the lease term?

What is the issue?

Tier 1 and Tier 2 for-profit entities will be aware that for reporting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2019 the new lease accounting standard (NZ IFRS 16) will "go-live".For lessee’s, the primary impact is that the large majority of their current operating leases will be coming on-balance sheet, in a similar way to how finance leases are currently treated.

This will result in the recognition of:

- A liability – for future lease payments

- An asset – reflecting the lessee’s right to use the leased item.

To do this, the lessee needs to first establish three key inputs:

- The lease term over which lease payments will be made.

- The amount of those leases payments.

- The discount rate to use in determining the present value.

(Point’s 2 and 3 will be addressed in future articles.)

Determining the lease term... how hard can it be really?

An initial interpretation might be that:‘Isn’t the lease term simply the initial non-cancellable period which I have a contractual obligation to make lease payments over, and nothing more?’

In short, the answer to this is: ‘No, not necessarily’.

The thing to keep in mind is that NZ IFRS 16 is a principles based standard.

Accordingly, the resulting accounting aims to reflect the lease payments to be made over the period that the lessee is reasonably expected to require the use of the item, to which it has an enforceable right to.

To do this, a lessee therefore needs to include both the initial non-cancellable period, as well as considering any renewal and/or termination rights, and who holds those rights (i.e. the lessee and/or the lessor).

In considering renewal and/or termination rights, a lessee assesses all facts and circumstances, including for example:

- Economic incentives that are in play, such as.

- The existence of any direct contractual termination penalties.

- The presence of any inherent financial and practicable penalties.

- The lessee’s past practice with the same (or similar) leases.

To illustrate this, consider the following examples:

Example 1 – Lessee has the ability to terminate the lease after ‘X’ years

In this example, assume that under the lease agreement:- The contractual term is 10 years.

- The lease agreement contains a Termination Clause that permits the lessee to terminate the lease at each 2 year anniversary date.

- There is no (significant) termination fee payable to activate the Termination Clause.

In this example, the lessee has the sole ability to terminate the lease, so only the lessee’s facts and circumstances are considered.

Based on the above, there is no way to definitively determine what the lease term is. This will come down to the specific circumstances of the lessee.

Scenario a

For example, if the leased item was a commercial factory, with extensive fit out, in-place heavy manufacturing machinery, in a location that optimises the lessee’s operations, and ordinarily there is not a readily available supply of alternative site, it would be reasonably expected that few (if any) of the termination options would be exercised by the lessee.

This is because irrespective of there not being a direct contractual financial penalty, there are various inherent penalties (both financial (i.e. investment in fit out, relocation costs associated with in-place heavy machinery) and practical (i.e. physical relocation and upheaval of manufacturing operations) that would result in a reasonable expectation that the lessee would want to remain in this specific site for as long as possible.

Accordingly, in this case, a lease term closer to the maximum 10 year contractual term would be expected.

Scenario b

However, if for example the leased item was generic office space, with no extensive fit out, where optimisation of the lessee’s operations is not dependent on the location, ordinarily there is a readily available supply of alternative sites, and the costs of relocating are not significantly prohibitive, it may be that the lessee’s reasonable expectation is that it would exercise a termination option earlier rather than later during the contract term.

This is because there is no significant direct or inherent penalty associated with exercising the termination option.

Accordingly, in this case, the lease term closer to the 2 year non-cancellable period would not be unusual.

Example 2 – Both parties have the ability to terminate the lease after ‘X’ years

Assume the same facts as Example 1, but here the lessor also has the right terminate the lease at each 2 year anniversary date.What is the lease term?

In this example, both the lessee and lessor have the ability to terminate the lease, so the facts and circumstances of both the lessee and lessor are considered.

As with Example 1 above, there is no way to definitively determine what the lease term is. This will come down to the specific circumstances of both the lessee and the lessor.

The considerations regarding the lessee’s facts and circumstances are addressed above in Example 1.

In terms of the lessor’s facts and circumstances, the same economic incentive and past practice considerations would need to be made, including, for example”

- The availability of alternative lessee’s.

- Could a higher rental be achieved with a different lessee (i.e. economic incentive).

- Would significant costs be incurred in replacing the current lessee with a new lessee (i.e. refurbishment costs (including forgone rental income while being undertaklen), legal and marketing costs etc.).

Example 3 – The initial term is ‘X’ years and then continues until either party terminates

In this example, assume that under the lease agreement:- The initial contractual term is 5 years.

- After the initial contract term the lease can be cancelled by either party by giving 3 months’ notice.

- There is no (significant) termination fee payable to activate the Termination Clause.

In this example, the same considerations detailed above in Example 1 (for the lessee) and Example 2 (for the lessor) will need to be considered.

Because there is no contractually fixed end date to the lease agreement, the degree to which the lease term might extend beyond the initial 5 year term will be a significant area of management judgement.

This would also be the case for leases that are on rolling (monthly) renewal terms.

Why is determining the lease term so important?

The length of the lease term has a direct and consequential impact on the amounts initially and subsequently recognised across the financial statements in respect of a lease agreement.This is because the longer the lease term, the more lease payments will be included in determining the initial present values of the lease liability and the right-to-use asset.

With this in mind, with all other things being held equal, the longer the lease term:

- The higher the value of the liability and asset initially brought on-balance sheet.

- Year-on-year, the higher the total annual expense taken through profit or loss, noting that:

- Interest expense will be higher (i.e. higher absolute value of the associated liability)

- Amortisation expense will be lower (i.e. lower proportionate value of the associated asset)

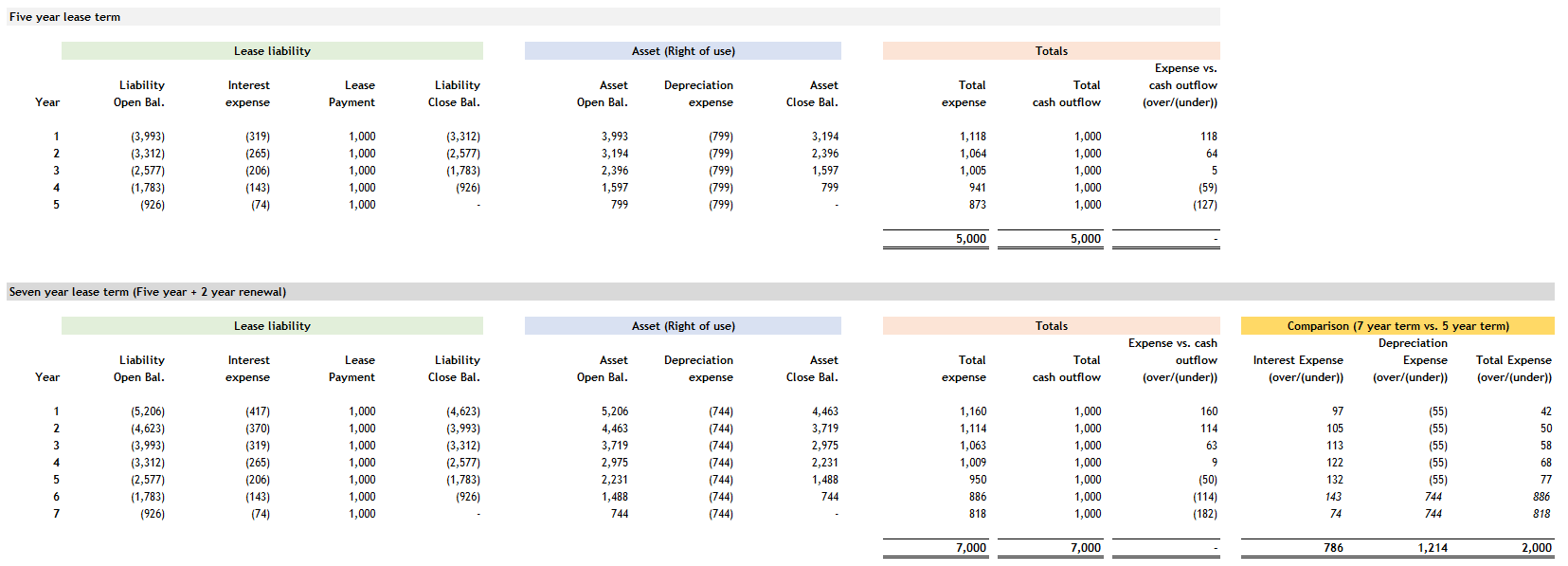

Lease details:

- The initial non-cancellable term is 5 years, with an renewal option for a further 2 years

- Lease payments are $1,000 per year in arrears

- The discount rate is 8%

- There are no other direct costs, restoration costs, prepayments, or lease incentives that impact the initial value of the asset.

- 5 years (with the present value of the lease payments of the 5 year lease term being $3,993)

- 7 years (with the present value of the lease payments of the 7 year lease term being $5,206)

The consequential impact of the determination of the lease term may thus be of particular relevance for those Tier 1 and Tier 2 for-profit entities:

- That are sensitive to various ratios and other financial metrics which are impacted by on-balance sheet treatment of leases (i.e. for bank covenants, staff and director bonuses, investor benchmarks etc.)

- On the cusp of breaching the ‘large’ criteria with respect to their asset base under legislation such as the Companies Act 1993 ($60m for New Zealand companies or $20m for subsidiaries and branches of overseas companies).